I really feel like I’m hitting my stride with these The Science Behind… posts.

After getting feedback from the first two, about sandwich bread and raspberry breakfast cake, I decided each post had maybe a little TOO much science. I don’t want these posts to be overwhelming to someone who is new to breadbaking. So for the next few posts, I’ll focus on one aspect of the breadbaking process or one ingredient or element.

If you haven’t already, please check out my post on hydration and baker’s percentages.

So now: let’s talk flour!

In this post, I’ll be discussing:

1. What is flour?

2. What are the types of flour and how are they different?

3. What happens to the flour when you make bread?

4. How can I use flour to change up a recipe?

Flour. It’s the most important ingredient in bread. Flour comes from grain that has been ground up into very small pieces, sometimes with one or more parts of the kernel removed so that the flour has a different taste, texture or protein level.

|

| close-up of wheat grains, or “kernels” |

2. The differences between flours can be chalked up to:

- The type of grain used (rye, wheat, spelt, corn, barley, buckwheat, etc.)

- What varietal of a particular grain is used. For example, two common varietals for wheat flour are hard red winter (highest protein content) and soft white wheat (low protein content).

- What part of the grain is used.

- Any additions to the flour (such as “self-rising flour”)

Take wheat, for example.

|

| I used to be able to buy whole wheat kernels at the Austin Farmer’s Market |

There are three parts to a grain of wheat:

|

| https://runnerbeans.files.wordpress.com/2010/04/wheat-berry-diagram.jpg |

Bran, Endosperm, and Germ.

Bran has lots of fiber, but not much protein. (hint: when you see me use the word protein, think “gluten” even though flour itself does not contain gluten but instead two proteins that form gluten in contact with water)

Germ has some protein, but not much.

Endosperm has high protein and high starch.

If you ground up all three together, you get whole wheat flour. If you remove the bran and germ, you get all-purpose or bread flour.

This is simplifying a lot, since some varietals of wheat have high protein content in their endosperm, good for all-purpose and bread flour, and some have low protein content, which is good for cake and pastry flour.

What about self-rising flour? This type of flour includes baking soda and baking powder already mixed in. However, since we want to be able to control how much of each is in our dough, and we want to guarantee that the baking powder and baking soda are fresh, it’s better to add it yourself. Skip the self-rising flour.

3. So what exactly happens to bread when it’s mixed into a dough?

It depends on the flour you choose and the type of bread you are making. For the purposes of this discussion, let’s assume we want to make a yeast bread like my recipe for 66% hydration bread, and not a quick bread like banana bread. If you want to read about what happens (or doesn’t happen) to flour in quick breads you can check out my post here.

Still with me?

Ok. For my typical bread using wheat flour, water, salt and yeast, the all-purpose flour and bread flour are interchangeable.

Since both all-purpose flour and bread flour are made of endosperm and contain high levels of protein and starch, they are the perfect medium for yeast bread. First, the sugary starch is yeast’s favorite food. So the yeast get to work chowing down on the starch and releasing carbon dioxide gas which makes the bread rise. Second, the proteins contained in endosperm, glutenin and gliadin, combine with water to form long protein strands called gluten. The gluten creates a net.to capture the carbon dioxide.

|

| bread flour creates very stretchy gluten strands |

The reason you can substitute all-purpose flour and bread flour in this recipe is because we use a small amount of yeast and give the gluten a long time to form. It forms naturally over time, meaning you don’t have to knead a great deal (or at all) in the beginning. If you are in a greater hurry, you would want to add more protein to speed the process along, and knead the dough more. You might want to use all bread flour, or a mix of bread flour and all-purpose flour.

High protein is good because it creates a stronger net to not only trap carbon dioxide, but provide greater structure for your loaf.

4. How can you change up your bread using flour?

Flour is a great way to change up your daily bread and keep things interesting.

If you want a particularly chewy bread, such as pizza, or very large holes in your dough, like for ciabatta or french bread, you will want high protein flour. Ciabatta and french bread are high hydration doughs, so structure is particularly important for preventing a watery mess.

Let’s say you are looking for greater flavor or more nutrition. You would use whole wheat, buckwheat or rye flour.

HOWEVER: these flours are LOW protein flour. Meaning they do not create a strong net of gluten. These doughs tend to do better in bread pans, which help contain them and assist with structure before they are baked, rather than in boule or baguette form. They also do better when allowed to rise slowly.

Something else to consider about using bread flour OR whole wheat when compared to all-purpose flour is that they both require more water than all-purpose flour, but for different reasons.

I have not had success making 100% rye loaves. I do like their flavor, so I might throw in 100g or so into an all-purpose flour loaf. You can read about my rye bread quest here.

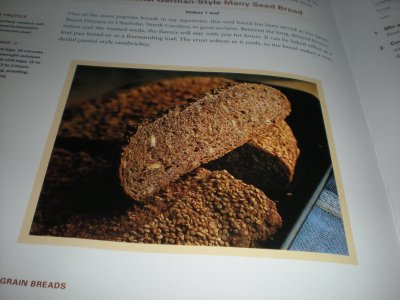

If you are interested, Peter Reinhart’s book on whole grain breads is fantastic.

Experiment! Throw 100g or so of rye, buckwheat, wheat germ or bran, or other flour into a basic bread flour or all-purpose flour dough and see if you can taste a difference.

If the taste of rye or whole wheat flour is too strong, experiment with honey to sweeten it or eggs, oil or milk to soften your dough.

Check out Peter Reinhart’s biga and soaker technique for getting the most flavor and rise from your whole wheat dough.

|

| Peter Reinhart’s whole wheat St. Lucia buns |

That’s it! I hope you have lots of ideas for changing up your dough and have learned a lot about flour!